In 1816, when it came time to commission a full-length statue of George Washington for the rotunda of the North Carolina State Capitol in Raleigh, Antonio Canova (1757-1822) was The Man. Finding American artists inadequate, Thomas Jefferson had looked to Europe. For him, only one person, the most famous Neoclassical sculptor of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, would do. In short order, Canova was commissioned to commemorate the first POTUS with a marble statue.

This exhibit is its story.

Displaying all Canova’s preliminary pieces and related works together for the first time allows us to trace his creative processes. Canova set to work in 1817. As was his habit, he produced sketches, drawings, and plaster and terracotta versions for his life-size plaster modello (model), the final interpretation before the marble sculpture. Canova completed his masterpiece in 1820.

After crossing the Atlantic, the 16-foot statue was pulled to Raleigh by a team of 12 oxen. Delivered with great fanfare in 1821, the sculpture would be destroyed by fire ten years later.

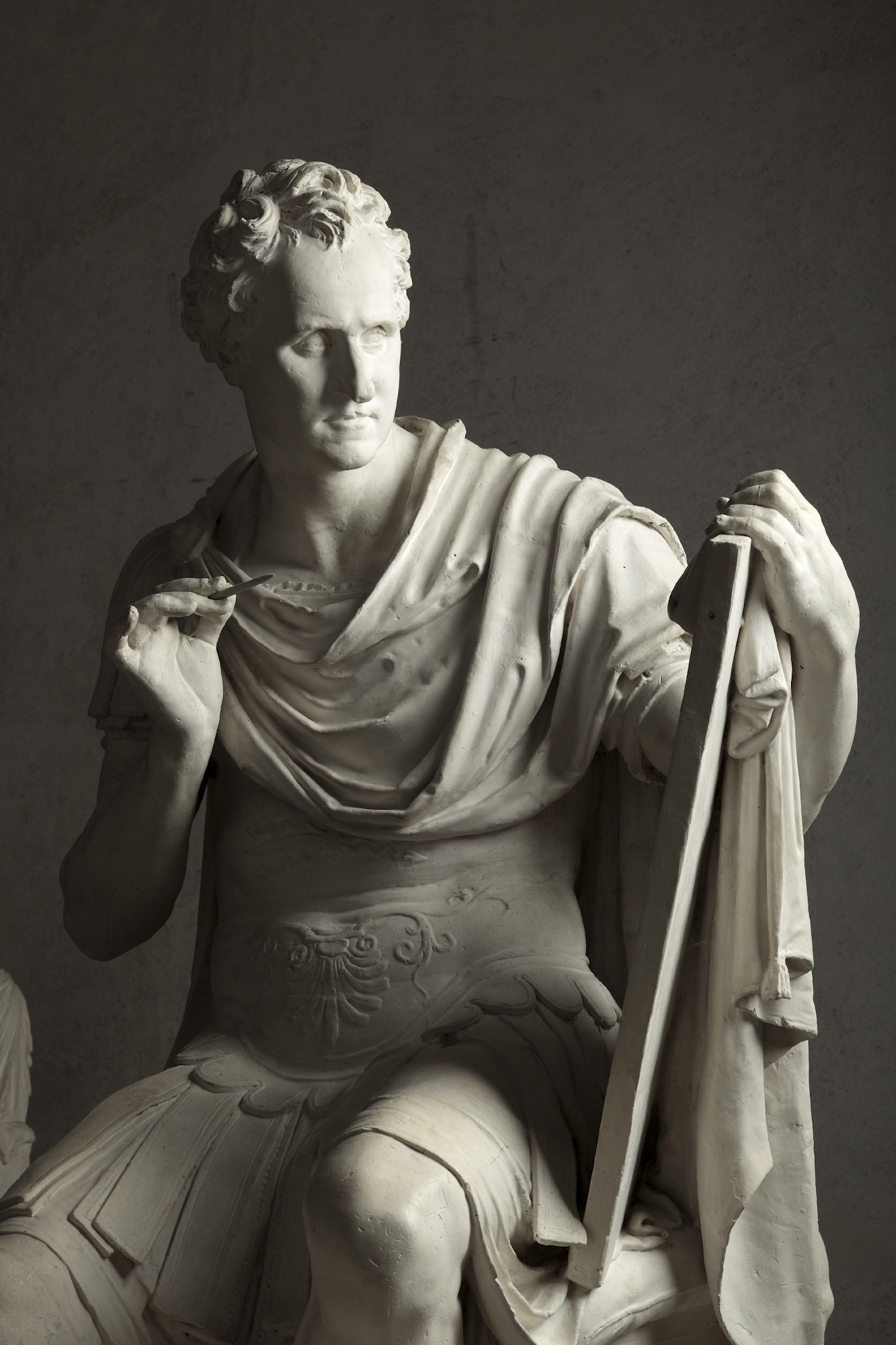

The closest approximation of the destroyed marble sculpture, the modello is shown to great effect by itself in the Frick’s Oval Room, which is similar to the rotunda for which it was designed. (Washington is seated because the ceiling of the rotunda was too low for a standing figure.) As we can see from the modello, which has never before left Italy, portraying Washington was problematic.

First of all, what to wear?

Led by Washington, America had fought a revolution for independence. To establish a national identity and to mythologize itself as an optimistic redeemer nation founded on narratives of equality and social mobility, America needed a symbolic central figure.

Paging George Washington.

Ancient garb provided a heroic quality that would help construct the legend. Both Canova and Jefferson pictured the statue in classical Roman costume. Although this was not unusual for the period, it was particularly appropriate here since many colonial American leaders knew ancient history and hoped that their new nation would emulate the best features of Greek and Roman republics. Fearing that contemporary clothing like velvet jackets or military uniforms would have a “puny effect,” Jefferson insisted on classical dress to elevate Washington.

Unlike most European emperors, popes, and monarchs, who would not voluntarily relinquish their positions, Washington had chosen to retire from the presidency. He was therefore often compared to Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the heroic ancient Roman dictator who retired to his farm after winning a war. Enhancing this comparison, Canova shows Washington drafting his farewell address to the nation. The paper in his hand reads: “Giorgio Washington/ Al Popolo degli Stati Uniti/1796/Amici e Concittadini” (George Washington/To the People of the United States/1796/Friends and Citizens.) It is rather ironic that Washington here refers to himself as Giorgio and writes to the new nation in Italian!

Even more problematic was the representation of Washington’s likeness since Canova had never seen Washington, who had died some sixteen years earlier. The models Canova considered working from are displayed in the East gallery, which adjoins the Oval Room. These include sculptures by Jean-Antoine Houdon, made from a life mask, and by Giuseppe Cerracchi, made from life. After much deliberation, Canova settled on the Cerracchi bust of a sixty-year-old Washington. Canova had rejected paintings by Gilbert Stuart, who had drawn some hundred likenesses. (The Frick’s is on view.) Perhaps because one of them graces the dollar bill, Stuart’s iconic Georges are the most recognizable images of Washington today. They bear little resemblance to Canova’s portrayal.

Besides the modello, the most interesting piece on view has got to be full-frontal George. Dubbed “Naked George,” this 30-inch nude model was in preparation for the marble sculpture. Canova typically made preliminary naked plaster representations of his subjects to envision how the body functioned beneath garments.

Accompanying the exhibit is a beautiful new book Canova’s George Washington by Xavier F. Salomon, Curator of the Frick, who organized the show, with Guido Beltramini and Mario Guderzo. An Appendix features transcriptions of contemporary correspondence (including letters to and from both Jefferson and Canova) regarding the commission, creation, and transportation of the sculpture.

It is salutary to have this exhibit celebrating transatlantic connections and the first President of the United States in light of today’s relentless undermining of American diplomacy, democracy and the presidency itself by Donald Trump.

If you miss the Frick exhibit, take heart. This fall it is moving to the Gypsotheca e Museo Antonio Canova in Possagno, Italy, Canova’s birthplace.

Canova’s George Washington is at the Frick Collection, New York from 23rd May to 23rd September 2018.